Episodes 36 and 37 - Forced Labour

For Labour Day, we wanted to highlight the conditon of workers who aren’t protected by modern labour laws and labour unions. Given its prevalence throughout the world, we chose to examine the cross-cutting theme of forced labour.

We brought back Alexandra Sundarsingh for Part One, to bring historical context. Lex is a second year PhD student in the department of history at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She has a BA and MA from the University of Toronto. Thematically, her research interests include the history of Indian indenture, and its intersections with labor, race, gender, diasporic Indian culture, colonialism, and empire. Geographically, she focuses on how South Asia and the Indian Ocean world connect to broader global histories of migration, labor, and culture. She approaches these topics mainly through legal documentation and debates, transportation and labor infrastructure, and print culture in the Indian Ocean British colonies between 1840 and 1920. She also has an ongoing love of and interest in food history and hopes to be able to use this in her research as well. Check out her work here!

Lex recommended another book for this episode: We, the Survivors by Tash Aw

Excerpt from Amnesty International’s “Turning People into Profits” (p.7):

When Suresh, aged 39, first considered leaving his village in Saptari district for a foreign job, he hoped it might be a life-changing experience that would set him and his family up for a more secure financial future. His first step was to contact an agent in his village who knew about job opportunities abroad. The agent had good news. He could offer him work in a Malaysian glove making factory. Pay would be relatively high, at RM 1800 (USD 420) per month, and conditions would be good, with one day off every week, safe working conditions and clean accommodation. Ultimately, the agent said, this would give Suresh the chance to save enough money to buy land for his family.

But this chance would cost: Suresh had to pay the village agent, as well as the Kathmandu recruitment agency who would finalise the deal, upfront. To get his job, Suresh borrowed NPR 250,000 (USD 2,416) from a local moneylender, at an annual interest rate of 36%. Although the recruitment fee was enormous (and illegal), Suresh’s agent and the Kathmandu agency assured him that he would be able to quickly pay off the debt once he started earning in Malaysia. The reality was very different. At the glove making factory, Suresh was unpaid for months on end, and when he was paid, his employer made a number of unexplained deductions from his salary. Suresh could not leave and get a new job, because his passport had been taken away, and his employer refused to end his contract or even allow him to leave the factory. In desperation, Suresh turned to his recruitment agency for help. They did not return his calls.

Instead of making money, when Suresh finally returned to Nepal in 2015 he had accumulated a staggering debt of NPR 550,000 (USD 5,317).[1]

What is forced labour?

Forced labour is a form of modern slavery. It includes slavery, practices similar to slavery, and bonded labour/debt bondage. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), forced labour is: “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”. The ILO definition includes two core elements.

First, labour must be extracted under the menace of any penalty. The penalty can be penal sanctions or a loss of rights and privileges. In its most extreme form, the menace of a penalty can involve physical violence or restraint. But other, more subtle, forms of penalty exist as well. Sometimes that might mean denouncing victims to the police or immigration authorities. Penalties can be financial, as in the case of debt-bondage and wage theft. In other cases, people may have their documents confiscated.

Second the work must be of an involuntary nature. For this criterion, the ILO looks at things like the method and content of consent, any external constraints or indirect coercion, and whether it is possible to revoke freely given consent. It is often the case that victims enter forced labour situations initially of their own accord and discover later that they are not free to withdraw their labour. (FYI, the ILO definition excludes prison work.)

Debt bondage is a particularly prominent feature of forced labour in current-day contexts. Half of forced labour imposed by private actors included debt bondage. In agriculture, domestic work, and manufacturing, debt bondage was even more prevalent – occurring in more than 70% of cases.

Forced labour is different than sub-standard or exploitative working conditions – so, even though things like low wages or unsafe working conditions are exploitative and bad, they are not in themselves forced labour.

There are numerous international treaties on forced labour, including: ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29); ILO Forced Labour Protocol (ratified, not yet in force); UN Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery; Palermo Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children.

How it works

This short video does a good job of showing how forced labour often happens.

There are two main phases of forced labour: recruitment and control and exploitation.

Forced labour usually involves some kind of unfree recruitment, involving deception or coercion. Coercive recruitment often involves debt bondage or confiscation of documents. It can also occur through abuse of a difficult financial situation, irregular migrant status, or a difficult family situation. Deceptive recruitment is where promises made at the time of recruitment are not fulfilled. Victims are most commonly deceived about wages, working conditions, the jobs themselves, or the length of stay.

People in situations of forced labour work under exploitative conditions. This can include low salaries, delayed payments, imposed poor living conditions, excessive work, and lack of social protection. Victims of forced labour face coercion, which might include:

● Threats or actual physical harm

● Restriction of movement or confinement to the workplace or a limited area

● Withholding wages or excessive wage reduction that violates previously made agreements

● Retention of passports and identity documents

● Threats of denunciation to the authorities, when the worker has an irregular immigration status

What is the scale of forced labour?

In total, about 40 million people around the world are in modern slavery. That is roughly the same as the population of Canada. Modern slavery includes forced labour and forced marriage. Forced labour makes up more than half of modern slavery. At any given time, an estimated 25 million people are victims of forced labour. For context, that’s roughly the same as the population of Australia. (15 million people were living in a forced marriage). Those estimates are from a study called the Global Estimates of Modern Slavery created in 2017 by the ILO, the Walk Free Foundation, and the International Organization for Migration.

And that’s at any given time. In the past five years, 89 million people experienced some form of modern slavery.

Somewhere between 83% and 90% of the world’s forced laborers are working for the private sector, according to one estimate. Forced labour generates annual profits of about $150 billion USD.

State-imposed forced labour

State-imposed forced labour is declining as a source of forced labour, but it does occur. At least 2.2 million people worldwide are trapped in state- or rebel-imposed forms of forced labour. This form of forced labour often occurs in prisons or in work imposed by rebel or armed forces.

You can think about child soldiers as an example of state- or rebel-imposed forced labour. In previous episodes we have also talked about the Uzbek government’s connection to forced labour in the cotton industry. And of course, forced labour in Chinese re-education camps for Uighurs has received a lot of attention recently.

Another example is North Korea’s overseas workers program. North Korea sends somewhere between 50,000 and 120,000 of its citizens to work overseas and the government receives the lion’s share of wages for these workers (70-90%). North Korean overseas workers are primarily in China and Russia, although they have been found in dozens of countries in Asia, Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe. They are employed mostly in mining, logging, textile, and construction.

The United Nations and others have documented conditions that amount to forced labour. For instance: workers do not know the details of their employment contract; they receive tasks according to their state-assigned social class; they are under constant surveillance while working abroad; and they are threatened with repatriation if they commit infractions. It is believed that the North Korean regime makes $1.2 to 2.3 billion annually from its overseas worker program.

In the second episode, Kyla talks about the Chinese prison system and Christmas Light production. It’s pretty grim, but you can follow the link to read more. She also mentions the stories that have come out in the past few years of consumers finding notes in their merchandise from people experiencing forced labour, and you can read more about that here.

Where is forced labour a problem?

Modern slavery occurs everywhere, although forced labour is most prevalent in Asia and the Pacific, where 4 out of every 1,000 people were victims. Europe and Central Asia was the region with the second highest prevalence of forced labour (3.6 per 1,000), followed by Africa (2.8 per 1,000), the Arab States (2.2 per 1,000), and the Americas (1.3 per 1,000).

Forced labour happens in a bunch of industries, especially: domestic work; construction; manufacturing; agriculture, forestry, and fishing; accommodation and food services; wholesale and trade; personal services; mining and quarrying; and begging.

Source: Global Estimates of Modern Slavery 2017, p.32

There are some regional patterns to this. In the Middle East, for instance, forced labour is most often for domestic work (270,000 out of 400,000 according to the ILO). In developed economies, forced labour is more common in other sectors like agriculture, construction, and manufacturing.

An American study created a typology of sex and labor trafficking using data from a human trafficking hotline. The typology includes 25 categories of work, many of which are related to sex. According to the US Department of Labor, the goods with the most forced labor listings (meaning number of countries listed) are: bricks, cotton, garments, cattle, and sugarcane.

Who is affected by forced labour?

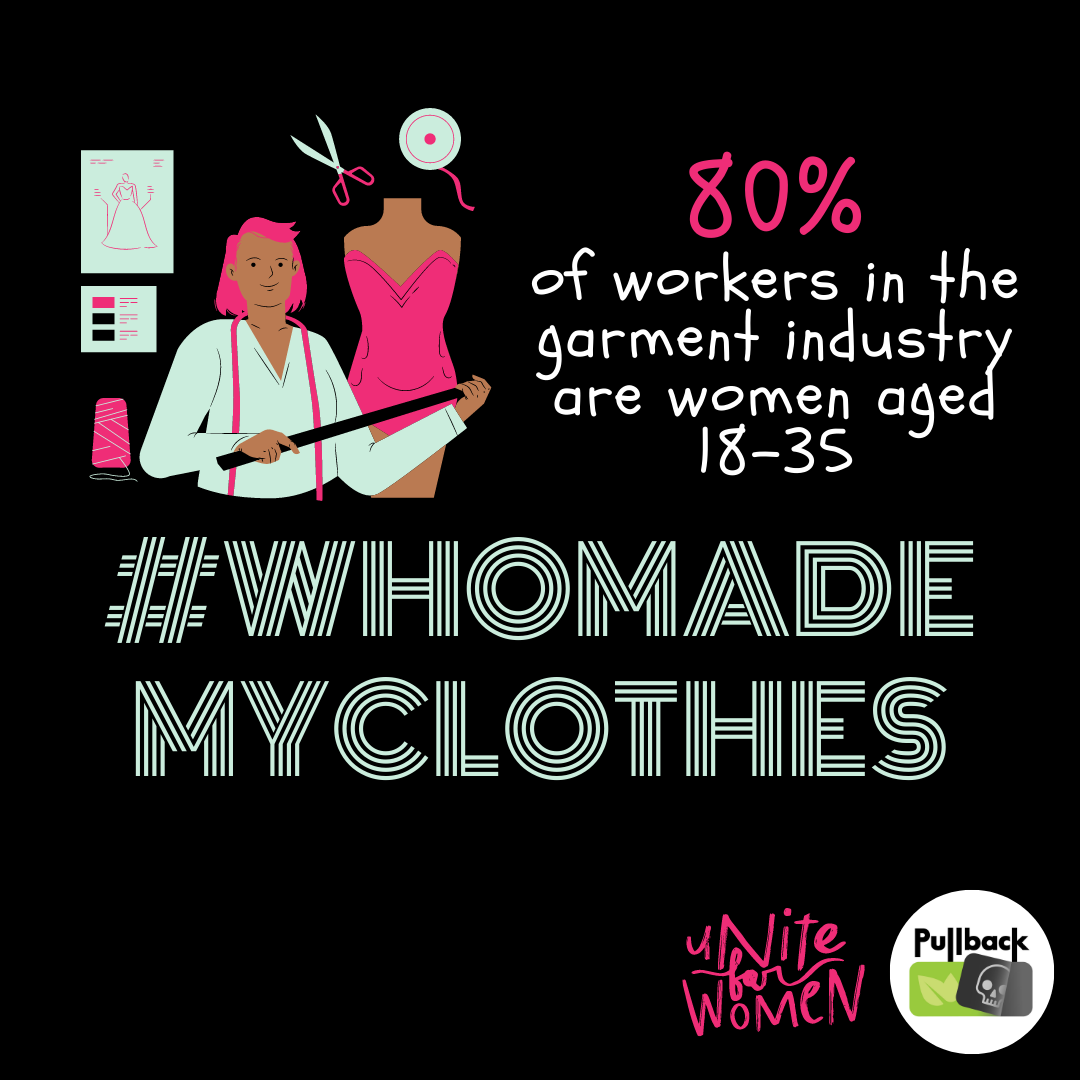

More than two-thirds of modern slavery victims are women and girls (71%). It’s true that some of this is because forced labour in the commercial sex industry is overwhelmingly women and girls (99%) and because women and girls are mostly the victims of forced marriages (84%).

But even in other sectors, women and girls make up more than half (58%) of forced labour victims. There are a few sectors where males are primarily victims of forced labour: mining and quarrying; begging; construction and manufacturing; and agriculture, forestry, and fishing. On the other hand, victims are most often women in domestic work and accommodation and food services.

Victims of forced labour tend to be younger than the workforce overall. About one fifth of forced labour victims are children (18%), although state-imposed forced labour uses children less frequently (7%).

Even though sexual exploitation is only about one-fifth of all forced labour, in terms of the number of people affected, two-thirds of profits from forced labour were generated by forced sexual exploitation. That is because sexual exploitation is the most lucrative form of forced labour, with an average annual profit per victim of $21,800 USD (compared with $4,800 in construction, $2,500 in agriculture, and $2,300 in domestic work). On the other hand, while forced labour in the agriculture, fishing, and forestry sector makes up a fairly small component of profits from forced labour, it affects quite a lot of people – approximately 3.5 million in 2014.

According to the Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline, some groups are most at-risk of forced labour. First are foreign nationals with precarious immigration status, recruitment debts, language barriers, and a lack of awareness of their rights. Second are those working in: agriculture and farming (seasonal workers, farm hands); domestic service (child/elder care and home housekeeping); hospitality (hotel housekeeping, restaurant kitchen work); construction and resource extraction (e.g., mining, timber, etc.); and services such as nail salons and commercial cleaning businesses. Third are people with vulnerabilities related to: precarious housing or homelessness, substance abuse, poverty, physical or learning disabilities, and mental health issues.

What are the causes of forced labour?

Poverty and globalization are two foundational causes of forced labour. But these are pretty broad concepts. To be a bit more specific, I want to talk about six dimensions that make people vulnerable to forced labour: restrictive migration regimes; economic vulnerability; sexism and racism; state fragility and conflict; authoritarianism; and global capitalism.

Restrictive Migration

Forced labour is closely connected to migration and, in particular, human trafficking. Almost one in every four victims of forced labour were exploited outside of their country of residence. This is especially the case for forced sexual exploitation, where three-quarters (74%) of victims were exploited outside of their country of residence. That is because there is a high degree of risk associated with migration, especially for migrant women and children.

Approximately 20% of forced labour is a result of human trafficking. Human trafficking is “the acquisition of people by improper means such as force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them.” People trafficked into forced labour are trafficked into commercial sexual exploitation (43%), economic exploitation (32%), and for mixed or undetermined reasons (25%).

Of course, it’s not just human trafficking: restrictive migration regimes can create unfreedom as well. Qatar’s successful bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup drew a lot of attention to the situation of migrant workers there. 95% of Qatar’s labour force consists of migrant workers, and these workers are brought in through a sponsorship system called the Kafala System. Qatar was roundly critiqued for this system, and international pressure led to changes. For instance, now workers do not require exit visas to leave the country. Although the Kafala System has been rightly criticized for how it creates the vulnerabilities that can allow for forced labour, what I found the most striking when I was reading about it is how similar it is to seasonal migrant worker programs in Canada and other wealthy countries. We mentioned COVID outbreaks among Canadian temporary workers and you can listen to more about that on this episode of Front Burner.

The ILO has a good description of how the vulnerability of migrant workers gets exploited in the construction industry in Eastern Europe, for instance:

Migrant workers are brought illegally to work on a construction site, without knowing the working conditions or terms of payment. There, they discover that they are forced to live together in a remote place provided by the employer (to avoid police controls) and told that they will be paid only at the end of the construction. A few days before the end, when the work is done and wages are due, the owner may call a law enforcement officer to inform him of the presence of irregular migrants. The workers are then deported and the employer does not need to pay them. All due wages (minus the bribe) increase the profits made.

Economic Vulnerability

Poverty and lack of outside options are important risk factors for forced labour. In addition to poverty, people can be more vulnerable to forced labour when their family has undergone an income shock or is experiencing food insecurity.

Lower education and literacy levels can also make workers more vulnerable to forced labour. Weak labour protections create pools of unprotected workers, “who face serious barriers to acting collectively and exerting rights”. Workers can be unprotected because their country lacks robust labour protections or because they are in a category of work that is unprotected. In particular, the expansion of precarious work makes people more vulnerable to forced labour. The ILO has estimated that more than 75% of the global workforce is in temporary, informal, or unpaid work: so, “only a quarter of workers have the security of permanent contracts”.

Sexism and Racism

Some people are made more vulnerable to forced labour because some part of their identity denies them rights and full personhood. Although different, intersecting forms of discrimination play a role in forced labour, sexism is one of the most prominent dimensions.

Authoritarianism

State-imposed forced labour is largely a product of authoritarianism.

State Fragility and Conflict

On the other hand, state fragility and conflict can create opportunities for rebels and criminal organizations (and sometimes the government) to carry out illegal exploitation of workers.

Global Capitalism

Several facets of our global economy create pressure within the market for exploitable forms of labour and create spaces for exploitation. A report by openDemocracy and the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute identifies four of what they refer to as “demand side” causes of forced labour: concentrated corporate power and ownership; outsourcing; irresponsible sourcing practices (E.g., fast fashion’s quick turnaround); and governance gaps.

Forced labour in global supply chains

The US Department of Labor produces a list of goods produced by child labor or forced labor. The most recent report is for 2018, and it is LOOOOOOOOOOOOOONG. Forced labour can appear in any industry, and can affect the supply chains or direct operations of companies of different sizes.

The top five products at most risk of modern slavery, according to the Walk Free Foundation, are:

Laptops, mobile phones, and computers ($200.1 billion in at-risk products imported into the G20);

Garments ($127.7 billion);

Fish ($12.9 billion);

Cocoa ($3.6 billion); and

Sugarcane ($2.1 billion).

Every year, over $34 billion in goods imported into Canada are “at a high risk of having been produced by child or forced labour.” “More than 1,200 companies operating in Canada were identified as having imported one or more of these high-risk goods.” For global figures, see the Global Slavery Index produced by the Walk Free Foundation.

Workers are particularly vulnerable to forced labour in the lower tiers of global supply chains – extracting raw inputs and processing them. While forced labour is a complicated challenge, it is possible for companies to monitor their supply chains to reduce the risk that they are complicit.

Preventing forced labour in global supply chains

Companies can work to prevent forced labour in their supply chains by having policies, knowing where in their supply chain there are risks of forced labour; having supplier codes of conduct and carrying out due diligence; and training staff to recognize forced labour.

What should you do about it?

Pick Leading Big Brands

You can try to look for brands that are taking action to address forced labour in their supply chains. But know that these leading brands have not eliminated forced labour.

For example, in 2019 the UK police uncovered the largest modern slavery operation in its history, involving 400 Polish trafficked workers. Some of those victims were employed by second-tier suppliers to major supermarket and building supply chains, including Tesco and Sainsbury’s – the two leading companies in Oxfam’s Supermarkets Scorecard for performance in protecting human rights.

Right now, there are no big brands that have truly eliminated forced labour from their supply chains. But there are companies that are doing much better than others.

The Stop Slavery Award recognizes companies with strong policies and processes to limit the risk of slavery in their supply chains and operations, as well as those acting as key agents in the global fight against slavery. Some previous winners include Apple, Unilever, Adidas, Intel, and Co-op.

Know the Chain’s benchmarking reports can help you find leaders and laggards in apparel and footwear; food and beverage; and information and communications technology.

Try Fairtrade

To the extent that Fairtrade labels are available, they can provide an alternative that is likely to be free from forced labour.

Fair trade is a set of movements, campaigns, and initiatives that have emerged in response to the negative effects of globalization. A product that is certified as Fairtrade has met a set of standards on pay, working conditions, and sometimes other social or environmental criteria. As we discussed in the Sugar episode, there are also fair trade member systems that work a bit differently.

However, there are some critiques of Fairtrade. Some see the use of fairtrade certification as “fairwashing” – meaning a way to superficially seem like a company is doing well on workers’ rights without actually addressing the problem. Critics tend not to argue that fair trade products are not living up to the standards established by certifying bodies. Instead, they argue that fair trade does not address the root causes of problems like forced labour.

Boycott?

A boycott can be tempting, but it is almost impossible and potentially counterproductive. In his TEDx Talk, a Foreign Affairs producer at PBS Newshour named P.J. Tobia recommends focusing on one product at a time and learning about how the supply chain works, what is causing forced labour in that issue, and what solutions are being proposed. Then you can support NGOs working on the problem or lend your voice to promote policy change or to push a company to change its practices.

Use Your Voice to Promote Human Rights

Another thing you can do is tell your representative that you care about ratifying the ILO Protocol on Forced Labour. The Protocol on Forced Labour is an international treaty. To enter into force, it needs 50 states to ratify and currently only 45 states have done so.

If ratified, the Protocol on Forced Labour would require governments to take new measures to address forced labour. For instance, countries will need to increase inspections to protect workers and guarantee victims access to justice and compensation. Canada has already ratified, but the United States and Australia both have not. You can find out more about the ILO Protocol on Forced Labour and how to get involved at the 50 for Freedom campaign website.

In Canada, tell your Member of Parliament that you want to see the Modern Slavery Act (Bill S-211) become law, but you want it to include: higher penalties, due diligence requirements, and a broader focus on human rights (in addition to child and forced labour). The Modern Slavery Act would create an obligation for companies to report to the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness on steps taken to prevent and reduce the risk of forced or child labour in any step of the production process. This Act is not as strong as its French and Dutch counterparts, but it is a good first step.

The UK’s Modern Slavery Act 2015 is the first such legislation, though other jurisdictions such as California and Australia now have similar laws. Most modern slavery laws only apply to large companies – for instance, only 150 companies are covered under the French legislation.

The Canadian Act was introduced for a first reading in the Senate in February. Read the report that spurred this legislation.

The Challenge

For our challenge, Kyla and I each looked at a specific good that has been linked to forced labour by the US Department of Labor. I chose rice. Kyla chose Christmas lights.

According to the US Department of Labour’s Sweat and Toil app, there has been forced labour documented in rice production in Burma, India, and Mali (as well as child labour in a few other countries).

India: debt bondage

In 2007, 24 people were rescued from a rice mill in India. They had been “abused and enslaved” there. The mill owner was convicted under India’s Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act in 2018. There is another story from 2019 where a pregnant woman named Soniya working in debt bondage at a rice mill lost her baby because of the harsh working conditions. Even though debt bondage is illegal in India, in the country’s 2011 census India identified more than 135,000 bonded workers. Of course, the real figure is likely a lot higher – International Justice Mission estimates 500,000 bonded labourers just in the state of Tamil Nadu.

Myanmar: state-imposed forced labour

In Myanmar, there are accounts of up to 8,000 Rohingya Muslims being forced into hard labour by soldiers. Rice production is one of the industries in which this kind of forced labour occurs.

Mali: descent-based slavery

For Mali, forced labour primarily happens in rice production because members of the Bellah or Ikelan community in Northern Mali are often enslaved by Tuareg communities. Tuareg society is an ethnically casted society with five tiers. Three tiers are perceived racially as “white”, according to an article by Baz Lecocq. The lowest two tiers are perceived racially as “black”, a grouping of craftspeople and then the unfree caste of slaves. Colonialism reinforced this hierarchical pyramid, particularly the links between race and bondage. Mali is one of three countries in Western Africa where Anti-Slavery International has undertaken initiatives to address descent-based slavery.

Endnotes

[1] Amnesty International. (2017). Turning People into Profits: Abusive Recruitment, Trafficking and Forced Labour of Nepali Migrant Workers. London: Amnesty International Ltd.